Blog

Research and Engineering

Iris recognition inference system

Iris recognition inference system

Worldcoin requires a system that can accurately verify one's uniqueness among billions of users. In this article, we will explain how our biometric pipeline processes iris images to enable uniqueness verification on a large scale.

Intro

As explained in our blog post Humanness in the Age of AI[1], it is becoming increasingly difficult to differentiate between people and bots online as AI technology advances. Worldcoin proposes a solution, using iris biometrics to verify humanness and uniqueness.

Worldcoin's use case in the field of iris recognition is quite unique. We are building a uniqueness verification system in an adversarial environment on a scale of billions of people. This is a technical deep dive on our biometric pipeline, the system that verifies uniqueness by encoding the iris texture into an iris code.

Pipeline overview

The objective of this pipeline is to convert high-resolution infrared images of a human's left and right eye into an iris code: a condensed mathematical and abstract representation of the iris' entropy that can be used for verification of uniqueness at scale. Iris codes have been introduced by John Daugman in this paper[2] and remain to this day the most widely used way to abstract iris texture in the iris recognition field. Like most state-of-the-art iris recognition pipelines, ours is composed of four main segments: segmentation, normalization, feature extraction and matching.

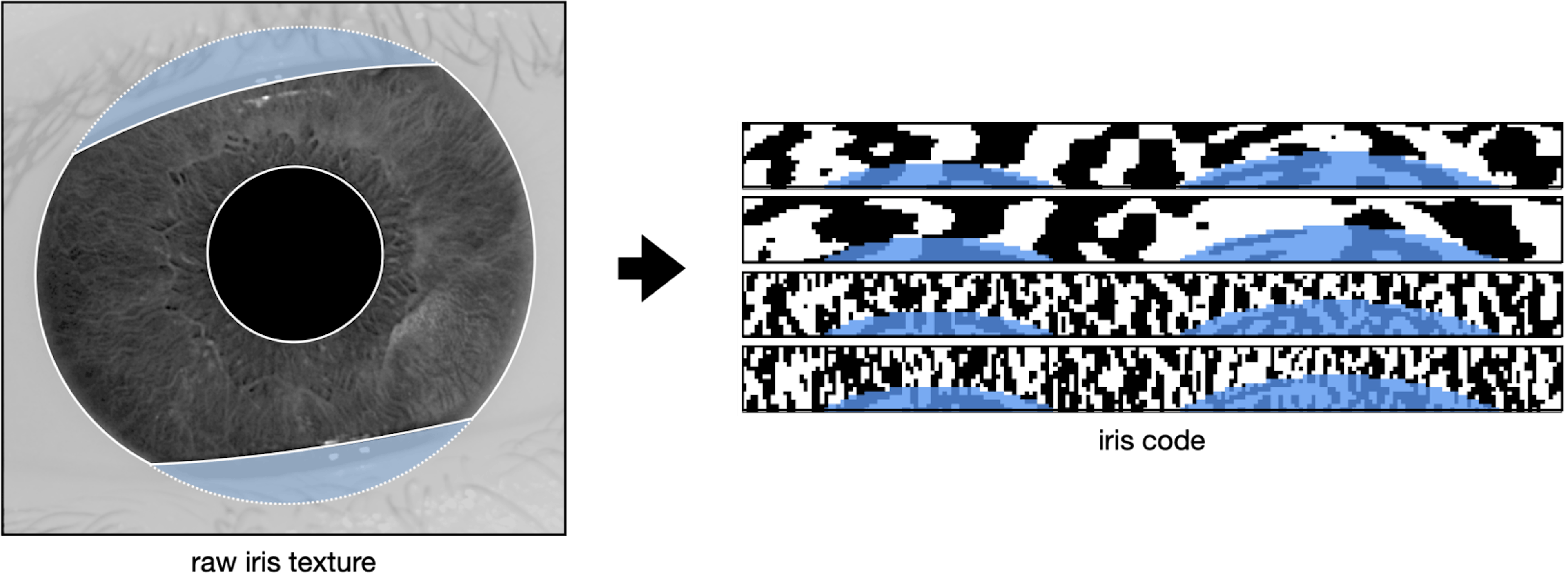

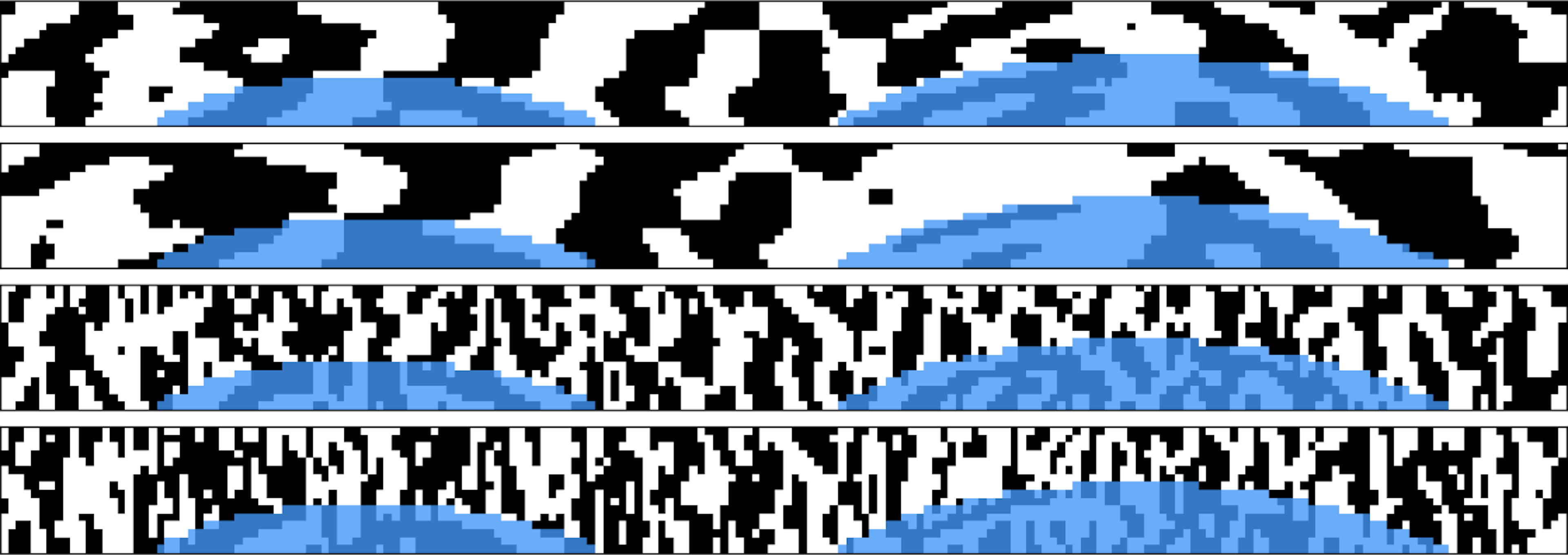

Refer to the image below for an example of a high resolution image of the iris acquired in the near infrared spectrum. The right hand side of the image shows the corresponding iris code, which is itself composed of response maps to two 2D Gabor wavelets. These response maps are quantized in two bits so that the final iris code has dimensions of , with and being the number of radial and angular positions where these filters are applied. For more details, see our blogpost on Iris feature extraction with 2D Gabor wavelets[3]. While we are showing only the iris code of one eye, note that an iris template consists of the iris codes from both eyes of the user.

Fig. 1

Example of an input and output of the biometric pipeline. Fig. 1.a is an example of an infrared iris texture image taken by the Orb. Fig. 1.b is an example of an Iris Code produced from the iris texture image in Fig. 1.a, effectively aggregating the iris texture.

In the segmentation step, we aim to understand the geometry of the input image. The location of the iris, pupil, and sclera are determined, as well as the dilation of the pupil and presence of eyelashes or hair covering the iris texture. Our segmentation model classifies every pixel of the image as pupil, iris, sclera, eyelash, etc. These labels are then post-processed to understand the geometry of the subject's eye.

The image and its geometry then passes through tight quality assurance. Only sharp images where enough iris texture is visible are considered valid, because the quantity and quality of available bits in the final iris codes directly impact the system's overall performance.

Once the image is segmented and validated, the normalization step takes all the pixels relevant to the iris texture and unfolds them into a stable cartesian (rectangular) representation.

The normalized image is then converted into an iris code during the feature extraction step. During this process, a Gabor wavelet kernel convolves across the image, converting the iris texture into a standardized iris code. For every point in a grid overlaying the image, we derive two bits that represent the sign of the real and complex components of the filter response, respectively. This process synthesizes a unique representation of the iris texture, which can easily be compared with others by using the Hamming distance metric. This metric quantifies the proportion of bits that differ between any two compared iris codes.

In the following sections, we will explain each of the aforementioned steps in more detail, by following the journey of an example iris image through our biometric pipeline. This image was taken on the Orb, our custom biometric imaging device developed by Tools for Humanity (TFH)[8] during a signup in our lab. It is shared with user consent and faithfully represents what the camera sees during a live uniqueness verification.

The eye is a remarkable system that exhibits various dynamic behaviors, including blinking, squinting, closing, as well as the ability of the pupil to dilate or constrict and the eyelashes or any object to cover the iris. In the following section, we will explore how our biometric pipeline can be robust in the presence of such natural variability.

Segmentation

Iris recognition was first developed in 1993 by John Daugmann (Daugman 1993[2]) and, although the field has advanced since the turn of the millennium, it continues to be heavily influenced by legacy methods and practices. Historically, the morphology of the eye in iris recognition has been identified using classical computer vision methods such as the Hough Transform or circle fitting (Daugman 2004[4]). In recent years, Deep Learning has brought about significant improvements in the field of computer vision, providing new tools for understanding and analysing the eye physiology with unprecedented depth.

We have proposed a novel method for segmenting high-resolution infrared iris images in Lazarski et al[5]. Our architecture consists of an encoder that is shared by two decoders: one that estimates the geometry of the eye (pupil, iris, and eyeball) and the other that focuses on noise, i.e., non-eye-related elements that overlay the geometry and potentially obscure the iris texture (eyelashes, hair strands, etc.). This dichotomy allows for easy processing of overlapping elements and provides a high degree of flexibility in training these detectors. The architecture takes into account the DeepLabv3+[6] architecture with a MobilNet v2 backbone.

Acquiring labels for noise elements is significantly more time-consuming than acquiring labels for geometry, as it requires a high level of precision for identifying intertwined eyelashes. It takes 20 to 80 minutes to label eyelashes in an image, depending on the levels of blur and the subject's physiology, while it only takes about 4 minutes to label the geometry to our levels of precision. For that reason we decoupled noise objects (e.g. eyelashes) from geometry objects (pupil, iris and sclera) which allows for significant financial and time savings combined with a quality gain.

Our model was trained over a mix of Dice Loss and Boundary Loss. The Dice loss can be expressed as

with being the one-hot encoded ground truth and the model’s output for the pixel as a probability. The third index represents the class (e.g. pupil, iris, eyeball, eyelash or background). The Dice loss essentially measures the similarity between two sets, i.e. the label and the model's prediction.

Accurate identification of the boundaries of the iris is essential for successful iris recognition, as even a small warp in the boundary can result in a warp of the normalized image along the radial direction. To address this, we also introduced a weighted cross-entropy loss that focuses on the zone at the boundary between classes, in order to encourage sharper boundaries. It is mathematically represented as:

with the same notations as before and being the boundary weight, which represents how close the pixel is to the boundary between class and any other class. We apply a Gaussian blur to the contour to prioritize the precision of the model on the exact boundary while keeping a lower degree of focus on the general area around it.

With being the distance between the point and the surface as the minimum of the euclidean distances between and all points of . is the boundary between class and all other classes, the Gaussian distribution centered at 0 with some finite variance.

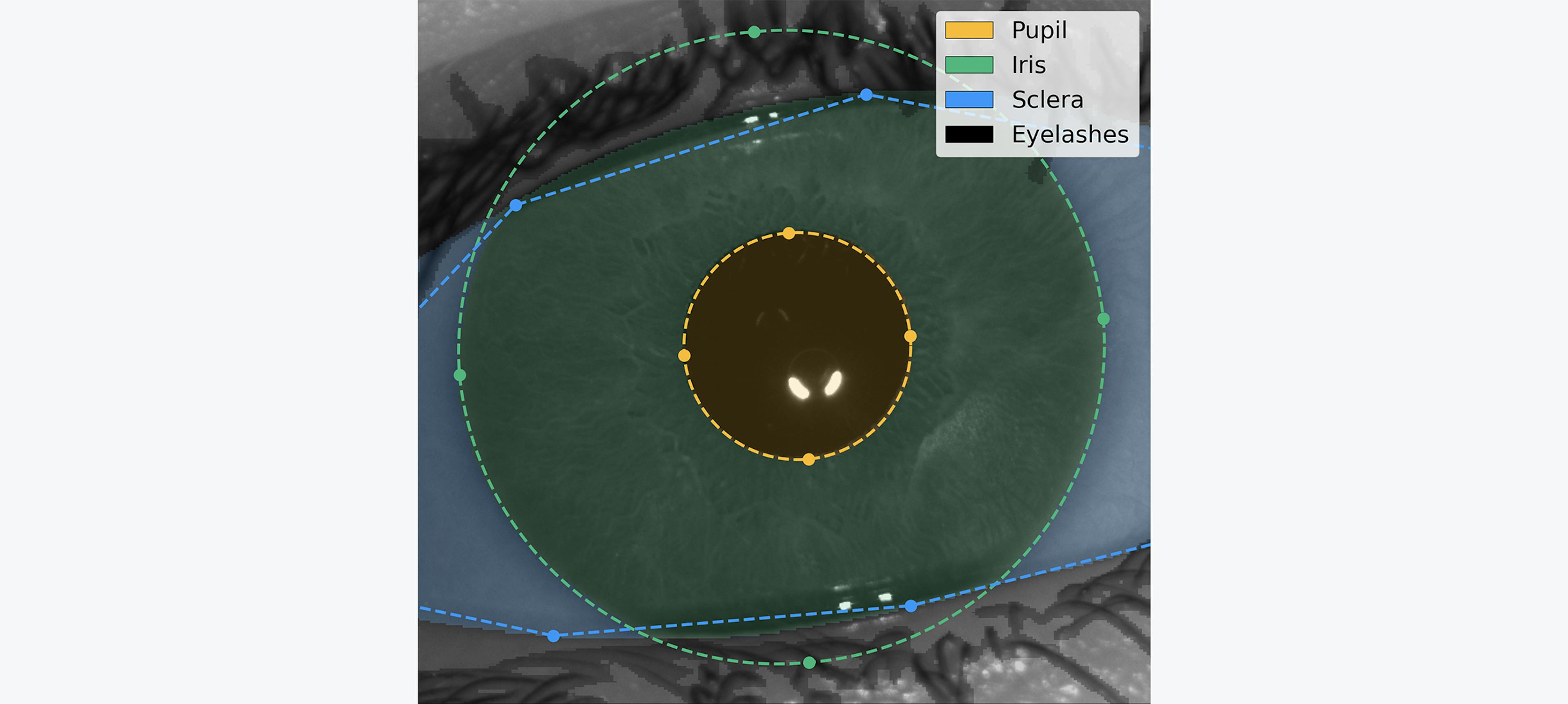

We conducted experiments with other loss functions (e.g. convex prior), architectures (e.g. single-headed model), and backbones (e.g. ResNet-101) and found that this setup had the best performance in terms of accuracy and speed. The following graph shows the iris image overlayed by the segmentation maps as predicted by our model. In addition, we display landmarks calculated by a separate quality-assessment AI model during the image capture phase. This model produces quality metrics to ensure that only high-quality images are used in the segmentation phase and that the iris code is extracted accurately for verification of uniqueness: sharp image focused on the iris texture, well-opened eye gazing in the camera, etc.

Fig. 2

Segmentation of an iris image. Our AI model detects the different regions of interest of the eye in order to isolate the relevant iris texture and assess the overall image quality. This is the result of an employee's signup done in our lab

Normalization

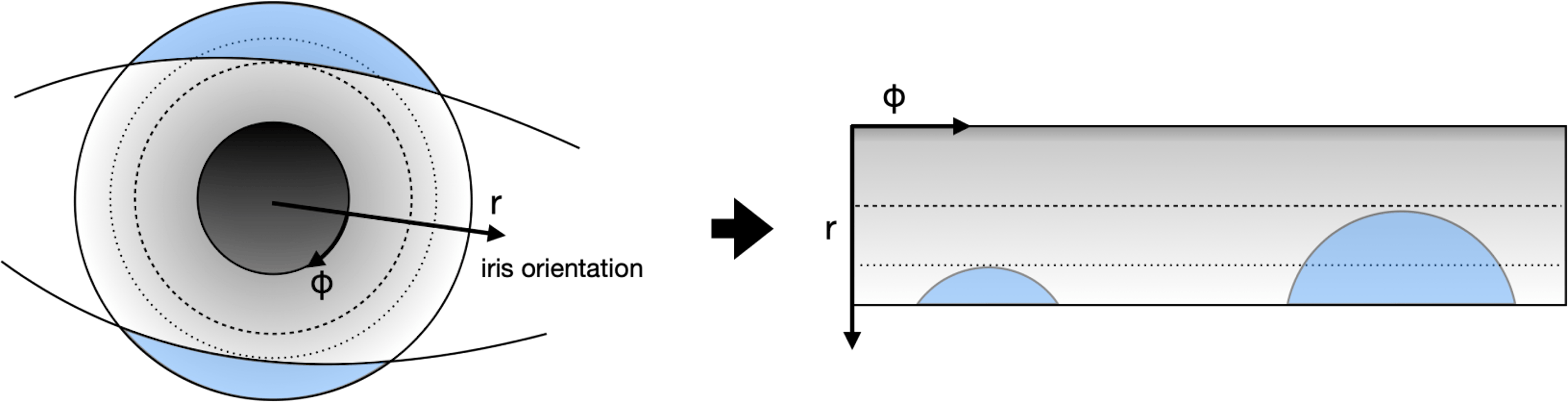

The goal of this step is to separate meaningful iris texture from the rest of the image (skin, eyelashes, eyeball, etc.). To achieve this, we project the iris texture from its original cartesian coordinate system to a polar coordinate system, as illustrated in the following image. The iris orientation is defined as the vector pointing from one pupil center to the other pupil center of the opposite eye.

Fig. 3

Scheme of the normalization process.

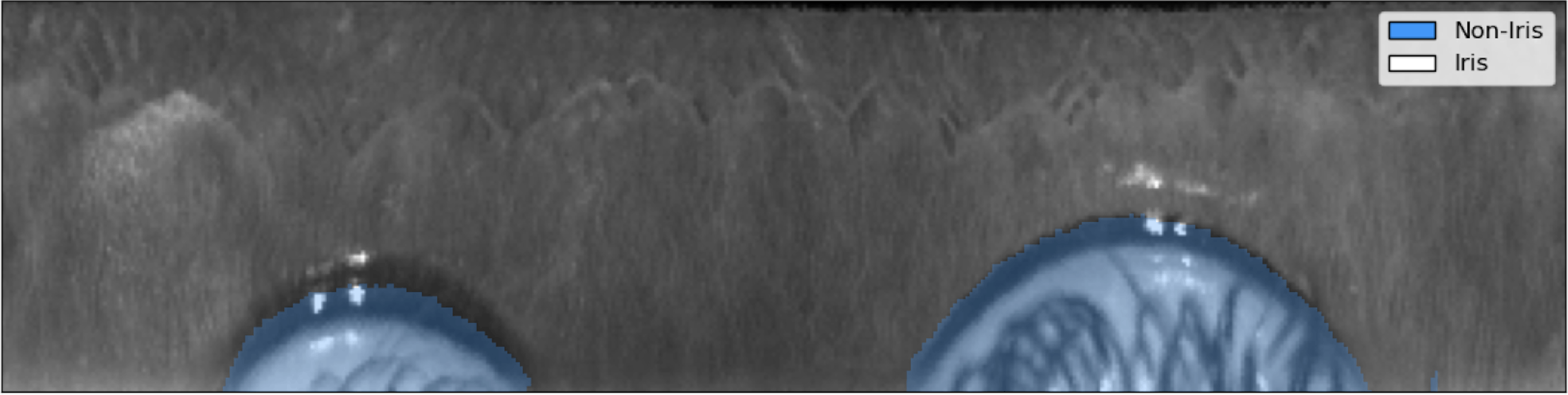

This process reduces variability in the image by canceling out variations such as the subject's distance from the camera, the pupil constriction or dilation due to the amount of light in the environment, and the rotation of the subject's head. The image below illustrates the normalized version of the iris above. The two arcs of circles visible in the image are the eyelids, which were distorted from their original shape during the normalization process.

Fig. 4

Normalized iris texture. The texture is sharp and its patterns are clearly visible.

Feature extraction

Now that we have produced a stable, normalized iris texture, we can compute an iris code that can be matched at scale. In short, we stride across the image with various Gabor filters and threshold its complex-valued response to extract two bits representing the existence of a line (resp. edge) at every selected point of the image. This technique, pioneered by John Daugmann, and the subsequent iterations proposed by the iris recognition research community, remains state-of-the-art in the field. We have dedicated a blog post to explaining this feature extraction method in more detail: Iris feature extraction with 2D Gabor wavelets.[3]

Fig. 5

Final iris code. This is the anonymized iris texture expressing one's uniqueness

Matching

Now that the iris texture is transformed into an iris code, we are ready to match it against other iris codes. To do so, we use a masked fractional Hamming Distance (HD): the proportion of non-masked iris code bits that have the same value in both iris codes.

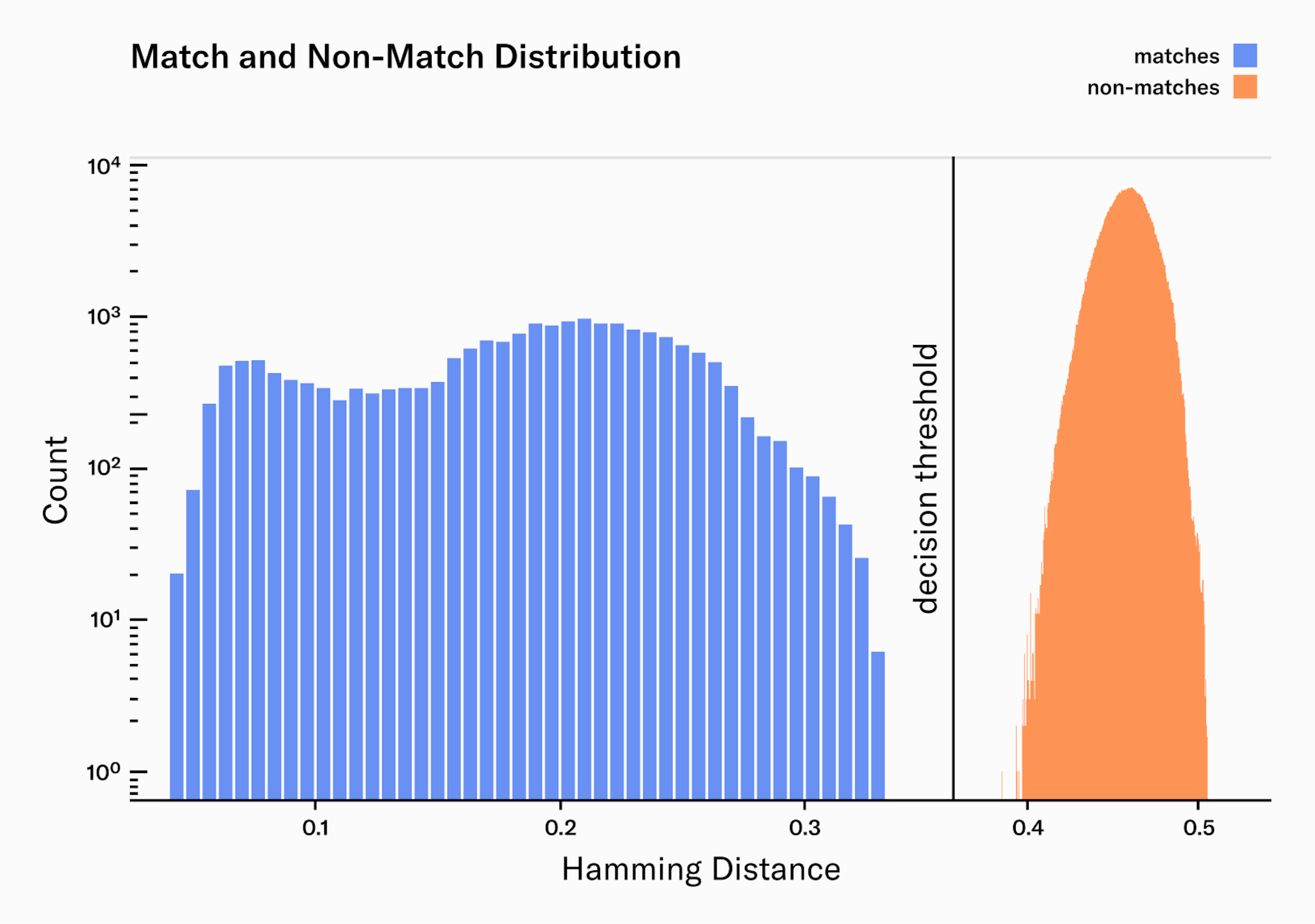

Due to the parametrization of the Gabor wavelets, the value of each bit is equally likely to be 0 or 1. As our iris codes are made of more than 10,000 bits, two iris codes from different subjects will have an average Hamming distance of 0.5, with most (99.95%) iris codes deviating less than 0.05 HD away from this value (99.9994% deviating less than 0.07 HD). As we compare several rotations of the iris code to find the combination with highest matching probability, this average of 0.5 HD moves to 0.45 HD, with a probability of being lower than 0.38 HD.

It is therefore an extreme statistical anomaly to see two different eyes producing iris codes with a distance lower than 0.38 HD. On the contrary, two images captured of the same eye will produce iris codes with a distance generally below 0.3 HD. Applying a threshold in between allows us to reliably distinguish between identical and different identities.

To validate the quality of our algorithms at scale, we evaluated its performance by collecting 2.5 million pairs of high-resolution infrared iris images from 303 different subjects. These subjects represent diversity across a range of characteristics, including eye color, skin tone, ethnicity, age, presence of makeup and eye disease or defects. Note that this data has not been collected during our field operations but stems from our team and from paid participants in a dedicated session organized by a respected partner. Using these images and their corresponding ground truth identities, we measured the false match rate () and false non match rate () of our system.

From our 2.5 million image pairs, all were correctly classified as either a match or non-match. Additionally, the margin between the match and non-match distributions is wide, providing a comfortable margin of error to accommodate for potential outliers.

The match distribution presents two clear peaks, or maxima. The peak on the left () corresponds to the median Hamming distance for pairs of images taken from the same person during the same enrollment process. This means that they are extremely similar, as you would expect from two images of the same person. The peak on the right () represents the median Hamming distance for pairs of images taken from the same person but during different enrollment processes, often weeks apart. These are less similar, reflecting the naturally occurring variations in the same person's images taken at different times like pupil dilation, occlusion and eyelashes. We are continuously working on improving our systems to narrow the matches distribution: better auto-focus and AI-Hardware interactions, better real-time quality filters, Deep Learning feature extraction, image noise reduction, etc.

As there were no misclassified iris pairs, we can not calculate the and exactly. However, we can estimate an upper bound for both rates:

With these numbers, we are confident that our system can reliably verify uniqueness on a billion people scale, which requires at least of and a reasonably low per eye. See Biometric Performance at a Billion People Scale[7] for more details. However, we acknowledge the fact that the dataset used for this evaluation could be enlarged and more effort is needed to build larger and even more diverse datasets to more accurately estimate the biometric performance.

Conclusions

In this article, we presented the key components of Worldcoin’s uniqueness verification pipeline. We illustrated how the use of a combination of deep learning models for image quality assessment and image understanding, in conjunction with traditional feature extraction techniques, enables the system to accurately verify uniqueness on a global scale.

However, our work in this area is ongoing. Currently, the team at TFH is researching an end-to-end Deep Learning model, which could yield faster and even more accurate uniqueness verification. Additionally, Worldcoin is continually improving its Presentation Attack Detection (PAD) models to counter various types of attacks, which leverage new models and sensors.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

Tanguy Jeanneau, Wiktor Łazarski and Christian Brendel