Blog

Research and Engineering

Iris feature extraction with 2D Gabor wavelets

Iris feature extraction with 2D Gabor wavelets

In this blog post, we discuss the traditional iris feature extraction method using Gabor filtering and why it works for iris texture.

Intro

Iris feature extraction aims to extract the most discriminative features from iris images while reducing the dimensionality of data by removing unrelated or redundant data. Unlike 2D face images that are mostly defined by edges and shapes, iris images present rich and complex texture with repeating (semi-periodic) patterns of local variations in image intensity[1]. In other words, iris images contain strong signals in both spatial and frequency domains and should be analyzed in both. Examples of iris images can be found on John Daugman's website.

Gabor filtering

Research has shown that the localized frequency and orientation representation of Gabor filters is very similar to the human visual cortex’s representation and discrimination of texture[2]. A Gabor filter analyzes a specific frequency content at a specific direction in a local region of an image. It has been widely used in signal and image processing for its optimal joint compactness in spatial and frequency domain.

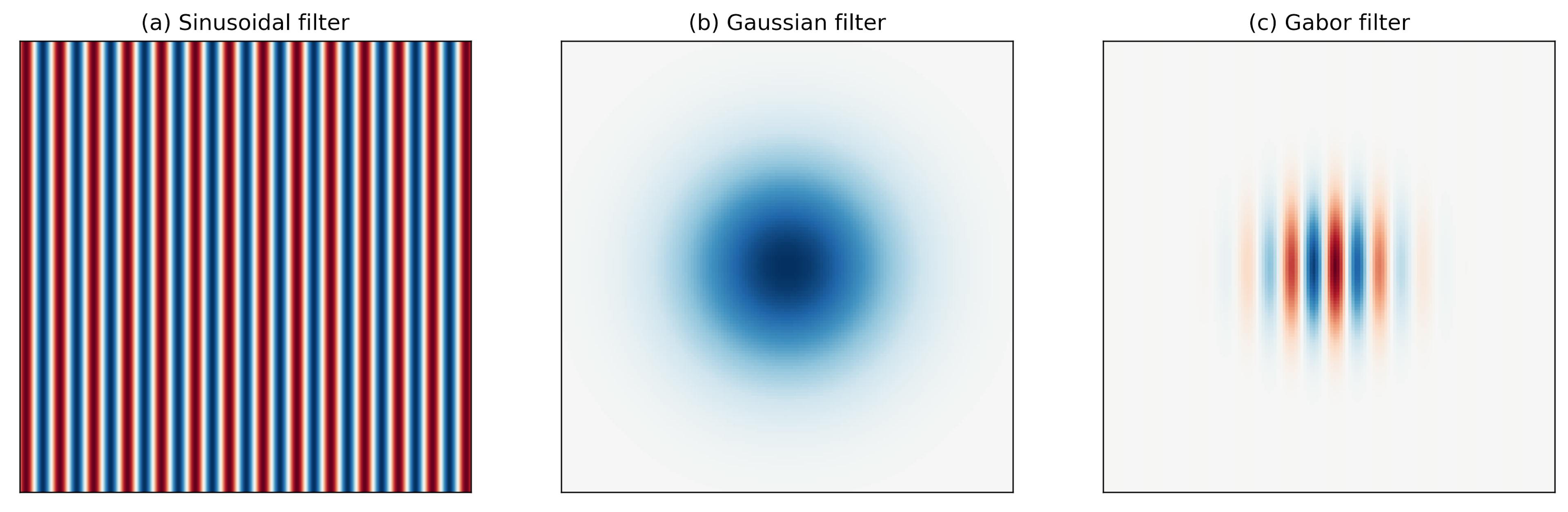

Fig. 1

Constructing a Gabor filter is straightforward. The product of (a) a complex sinusoid signal and (b) a Gaussian filter produces (c) a Gabor filter.

As shown above, a Gabor filter can be viewed as a sinusoidal signal of particular frequency and orientation modulated by a Gaussian wave. Mathematically, it can be defined as

with

Among the parameters, and represent the standard deviation and the spatial aspect ratio of the Gaussian envelope, respectively, and are the wavelength and phase offset of the sinusoidal factor, respectively, and is the orientation of the Gabor function. Depending on its tuning, a Gabor filter can resolve pixel dependencies best described by narrow spectral bands. At the same time, its spatial compactness accommodates spatial irregularities. For more details see[3].

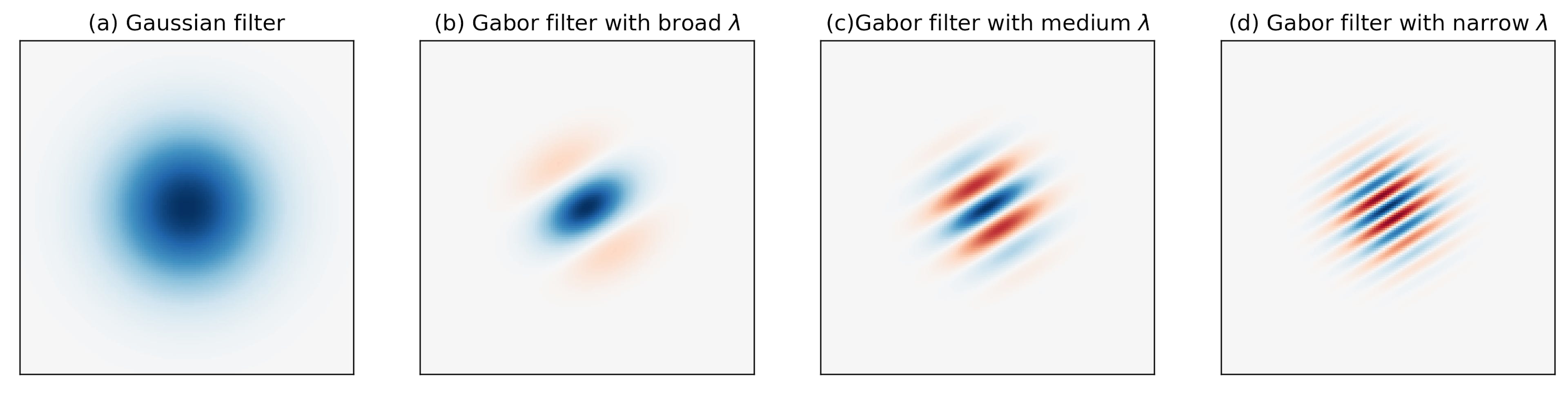

The following figure shows a series of Gabor filters at a angle in increasing spectral selectivity. While the leftmost Gabor wavelet resembles a Gaussian, the rightmost Gabor wavelet follows a harmonic function and selects a very narrow band from the spectrum. Best for iris feature extraction are the ones in the middle between the two extremes.

Fig. 2

Varying wavelength (a-d) from large to small can change the spectral selectivity of Gabor filters from broad to narrow.

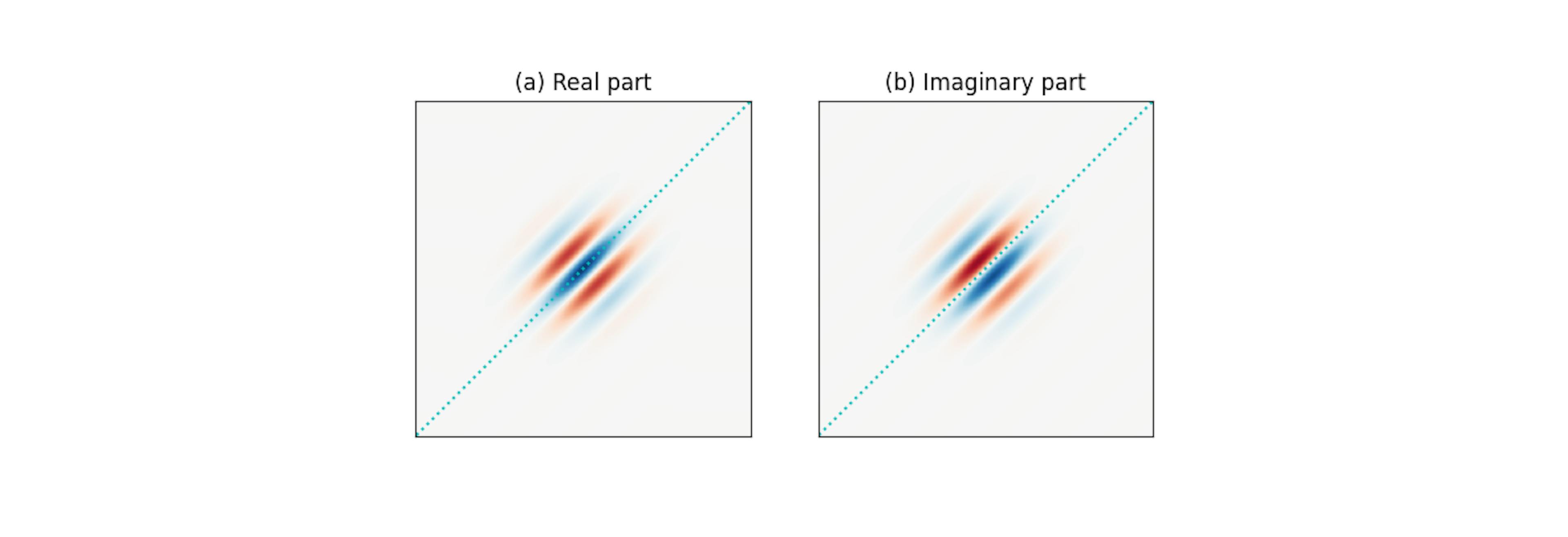

Because a Gabor filter is a complex filter, the real and imaginary parts act as two filters in quadrature. More specifically, as shown in the figures below, (a) the real part is even-symmetric and will give a strong response to features such as lines; while (b) the imaginary part is odd-symmetric and will give a strong response to features such as edges. It is important that we maintain a zero DC component in the even-symmetric filter (the odd-symmetric filter already has zero DC). This ensures zero filter response on a constant region of an image regardless of the image intensity.

Fig. 3

Giving a closer look at the complex space of a Gabor filter where (a) the real part is even-symmetric and (b) the imaginary part is odd-symmetric.

Multi-scale Gabor filtering

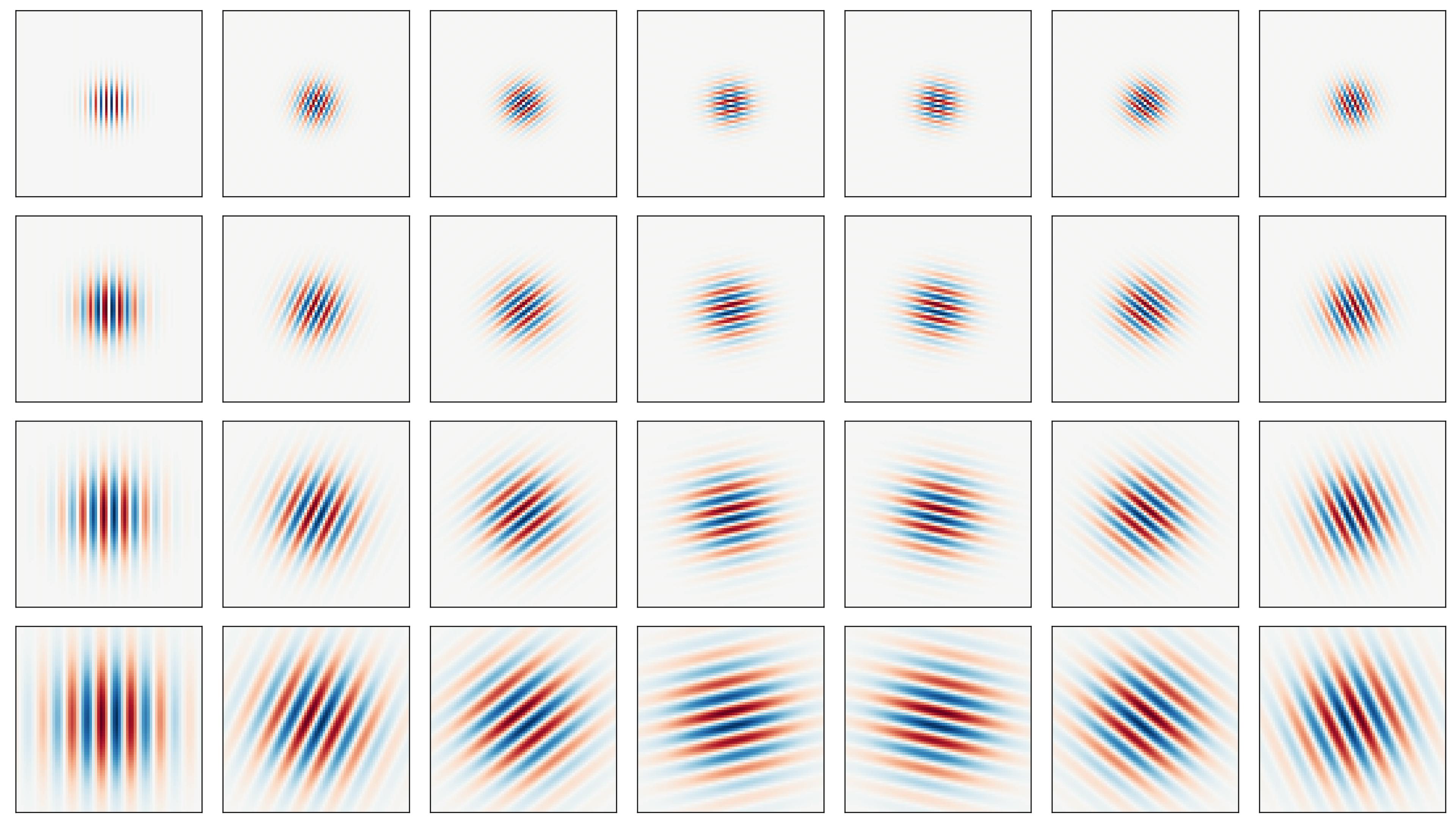

Like most textures, iris texture lives on multiple scales (controlled by ). It is therefore natural to represent it using filters of multiple sizes. Many such multi-scale filter systems follow the wavelet building principle, that is, the kernels (filters) in each layer are scaled versions of the kernels in the previous layer, and, in turn, scaled versions of a mother wavelet. This eliminates redundancy and leads to a more compact representation. Gabor wavelets can further be tuned by orientations, specified by . The figure below shows the real part of 28 Gabor wavelets with four scales and 7 orientations.

Fig. 4

Constructing Gabor wavelets with multiple scales (vertically) and orientations (horizontally) to extract texture features with various frequencies and directions.

In our feature extraction process, we use a small set of filters that concentrate within the range of scales and orientations of the most discriminative iris texture.

Phase-quadrant demodulation and encoding

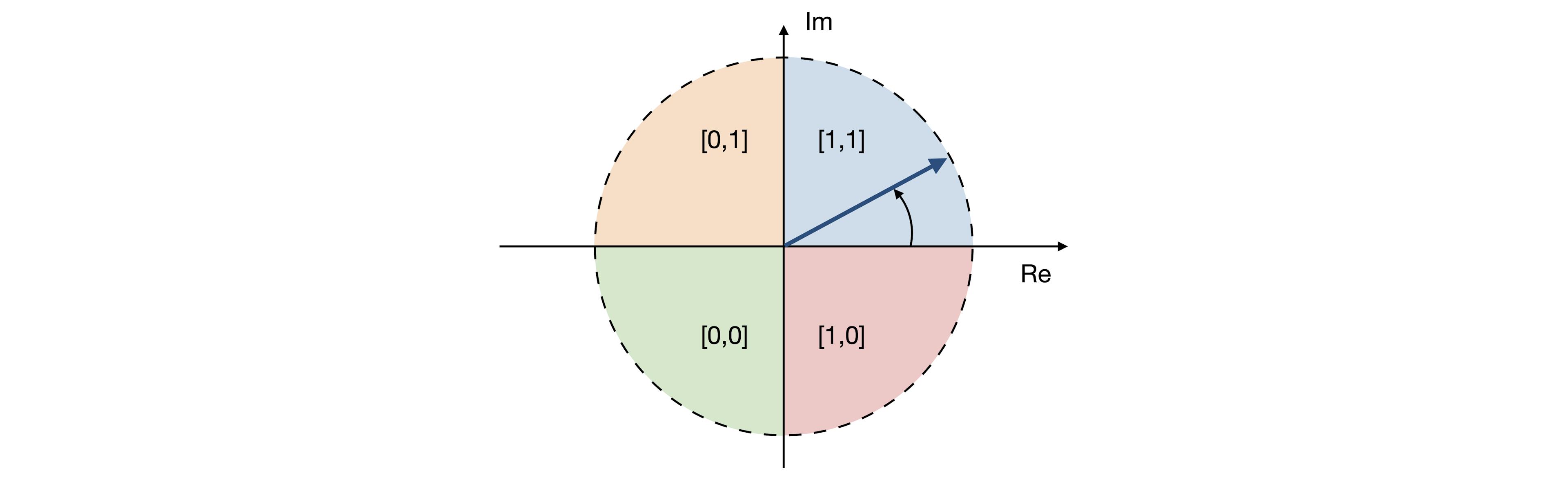

After a Gabor filter is applied to an iris image, the filter response at each analyzed region is then demodulated to extract its phase information[4]. This process is illustrated in the figure below, as it identifies in which quadrant of the complex plane each filter response is projected to. Note that only phase information is recorded because it is more robust than the magnitude, which can be contaminated by extraneous factors such as illumination, imaging contrast, and camera gain.

Fig. 5

Demodulating the phase information of filter response into four quadrants of the complex space. The resulting cyclic codes are used to produce the final iris code.

Another desirable feature of the phase-quadrant demodulation is that it produces a cyclic code. Unlike a binary code in which two bits may change, making some errors arbitrarily more costly than others, a cyclic code only allows a single bit change in rotating between any adjacent phase quadrants[4]. Importantly, when a response falls very closely to the boundary between adjacent quadrants, its resulting code is considered a fragile bit. These fragile bits are usually less stable and could flip values due to changes in illumination, blurring or noise. There are many methods to deal with fragile bits, and one such method could be to assign them lower weights during matching.

When multi-scale Gabor filtering is applied to a given iris image, multiple iris codes are produced accordingly and concatenated to form the final iris template. Depending on the number of filters and their stride factors, an iris template can be two to three orders of magnitude smaller than the original iris image.

Robustness of iris codes

Because iris codes are generated based on the phase responses from Gabor filtering, they are considered to be rather robust against illumination, blurring and noise. To measure this quantitatively, we add each effect, namely, illumination (gamma correction), blurring (Gaussian filtering), and Gaussian noise to an iris image, respectively, in slow progression and measure the drift of the iris code. The amount of added effect is measured by the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of pixel values between the modified and original image, and the amount of drift is measured by the Hamming distance between the new and original iris code.

Mathematically, RMSE is defined as:

where is the number of pixels in the original image and the modified image . The Hamming distance is defined as:

where is the number of bits (0/1) in the original iris code and the new iris code . A Hamming distance of 0 means a perfect match, while 1 means the iris codes are completely opposite. The Hamming distance between two randomly generated iris codes is around 0.5.

The following figures help us understand both visually and quantitatively the impact of illumination, blurring and noise on the robustness of iris codes. For illustration purposes, these results are not generated with the actual filters we deploy but nevertheless demonstrate the property in general of Gabor filtering. Also, the iris image has been normalized from a donut shape in the cartesian coordinates to a fixed-size rectangular shape in the polar coordinates. This step is necessary to standardize the format, mask-out occlusion and enhance the iris texture.

As shown in the figure below, iris codes are very robust against grey-level transformations associated with illumination as the HD barely changes with increasing RMSE. This is because increasing the brightness of pixels reduces the dynamic range of pixel values, but barely affects the frequency or spatial properties of the iris texture.

Fig. 6

Demonstrating the impact of illumination on the robustness of iris codes using Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) between images (blue line) vs Hamming Distance (HD) between corresponding iris codes (green line).

Blurring, on the other hand, reduces image contrast and could lead to compromised iris texture. However, as shown below, iris codes remain relatively robust even when strong blurring makes iris texture indiscernible to naked eyes. This is because the phase information from Gabor filtering captures the location and presence of texture rather than its strength. As long as the frequency or spatial property of the iris texture is present, though severely weakened, the iris codes remain stable. Note that blurring compromises high frequency iris texture, therefore, impacting high frequency Gabor filters more, which is why we use a bank of multi-scale Gabor filters.

Fig.7

Demonstrating the impact of blurring on the robustness of iris codes using Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) between images (blue line) vs Hamming Distance (HD) between corresponding iris codes (green line).

Finally, we observe bigger changes in iris codes when Gaussian noise is added, as both spatial and frequency components of the texture are polluted and more bits become fragile. When the iris texture is overwhelmed with noise and becomes indiscernible, the drift in iris codes is still small with a Hamming distance below 0.2, compared to matching two random iris codes (). This demonstrates the effectiveness of iris feature extraction using Gabor filters even in the presence of noise.

Fig. 8

Demonstrating the impact of noise on the robustness of iris codes using using Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) between images (blue line) vs Hamming Distance (HD) between corresponding iris codes (green line).

Summary

In this blog post, we discussed iris feature extraction as a necessary and important step in iris recognition. It reduces the dimensionality of the iris representation from a high resolution image to a string of binary code, while preserving the most discriminative texture features using a bank of Gabor filters. It is worth noting that Gabor filters have their own limitations, for example, one cannot design Gabor filters with arbitrarily wide bandwidth while maintaining a near-zero DC component in the even-symmetric filter. This limitation can be overcome by using the Log Gabor filters[5]. In addition, Gabor filters are not necessarily optimized for iris texture, and machine-learned iris-domain specific filters (e.g. BSIF) have potential to achieve further improvement in feature extraction and recognition performance in general[6]. Moreover, we are investigating novel approaches to leverage higher quality images and the latest advances in the field of deep metric learning and deep representation learning to push the state of the art in iris recognition.

As we showcased the resilience of iris feature extraction amidst external factors, it is crucial to note that even minor fluctuations in iris code variability hold significant importance when dealing with a billion people, as the tail-end of the distribution dictates the error rates, thus influencing the number of false rejections. We will elaborate further on this subject in an upcoming blog post.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Yi Chen, Tanguy Jeanneau and Christian Brendel